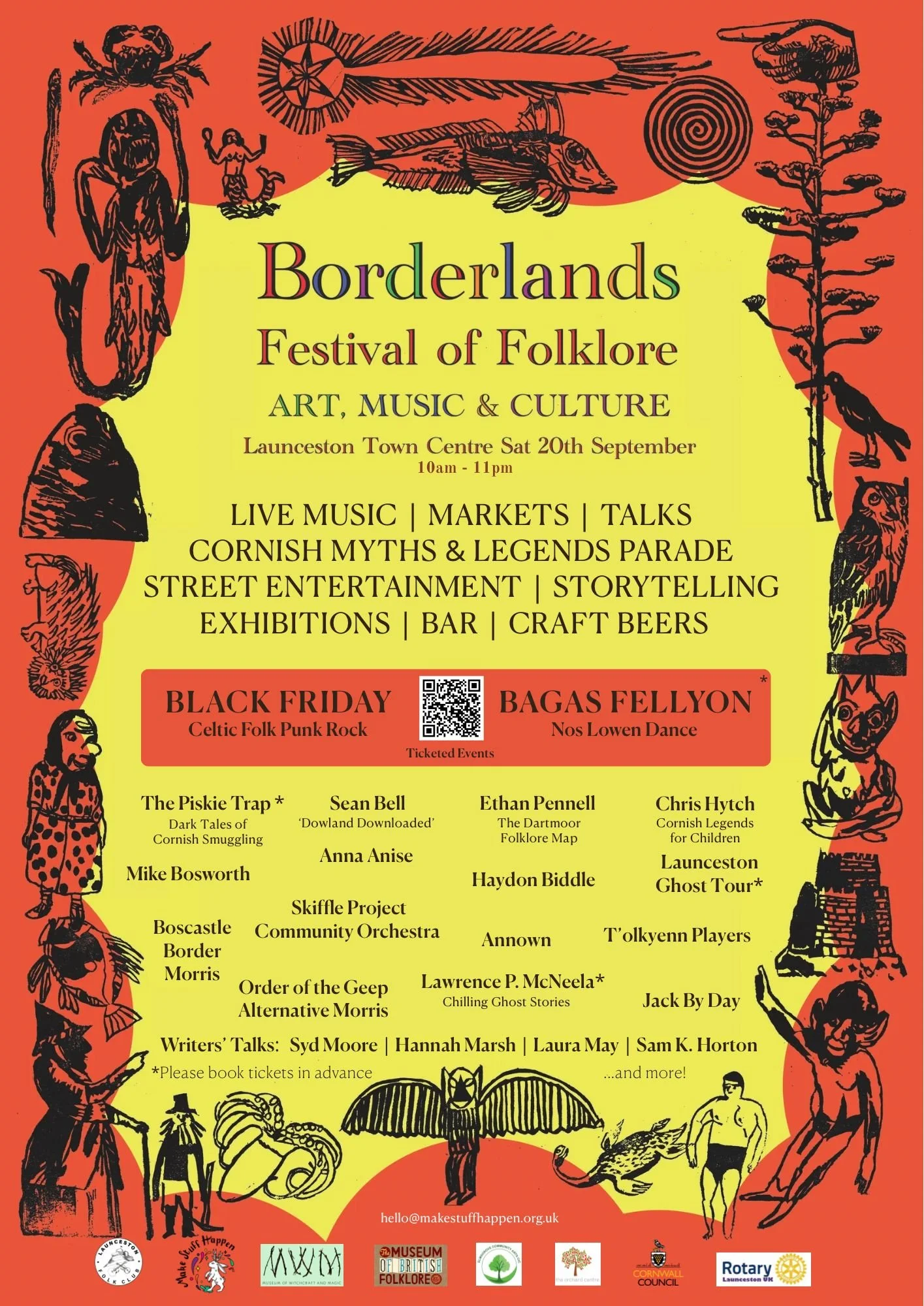

Borderlands

The First Borderlands festival.

A festival of folklore, art, music, and culture.

20th September 2025, Launceston, Cornwall.

A joint effort by Make Stuff Happen CIC, The Launceston Folk Club (and Wreckers Radio), The Museum of Witchcraft and Magic and Elmsgrove Community Arts CIC, as well as the many community-minded volunteers that gave their time to make this happen.

A story I penned for the promotional booklet promoting the first-ever Borderland Festival.

The First Festival

There is a hill in Launceston that remembers everything.

It remembers the time when giants argued over who owned the Tamar, hurling boulders across the valley like grumpy children with bad tempers. It remembers the Roman traders with thin smiles and fat purses. It remembers the Norman barons and the blood they spilt in the name of flags.

The hill doesn’t mind.

The hill just waits.

Once upon a not-so-long-ago, there was no Borderland Festival in Launceston. There was no singing on the wind, no stages built where music and magic mingle. But the border was still there—it always had been. And music—music lays at the foundation of this town.

The place where Cornwall ends and the rest of the world begins.

It’s not the last county. It’s the first.

The old folk say there’s a special kind of magic here. Often buried deep. Beneath the foundations of the castle, below the bones and rusted coins and secrets. A magic forged at the beginning of time.

When was the very first festival? Who could say? Even the Old Ones don’t know—those who danced long before Saxon or Celt, before Saint Stephen came with his church and his warnings.

To be human is to look up at the stars, wondering at life’s mysteries—and then share those thoughts.

People have always gathered together. Made merry. Sung songs. Told stories over the fire.

But one year, this year, someone dared to give it a name.

Borderland.

People started to talk. Who would come? Folk singers from Tavistock, maybe? A fiddle band from Bodmin? Poets from Penzance?

Some didn’t know how they’d heard about it—only that they had.

Locals were curious. Something in the bones of the town stirred.

The beech trees of Cookworthy Knapp called people home.

But is this really the first festival?

The hill knows the truth.

It had seen all that came before.

There was the time the first song was sung just after sunset, by a woman with a harp and a voice like rain. It drifted down the hill and across the rooftops of Northgate Street, and every sleeping child turned in their bed and dreamed of moonlight on standing stones. People heard the melody and came out to dance on the cobbles.

But that was not the first.

There was the time the birds gathered above the fauns, the naiads and dryads, as they danced beneath the early morning sun, long before the first humans stirred.

That also was not the first.

And then there was the time the hill echoed what was to come.

No one noticed the mist at first. It came gently, curling up from the river like breath from a hidden mouth. Not cold. Not threatening. Just… old.

It gathered in the lane behind St Mary’s church, pooled near the priory ruins, and wound its way up the castle path like it knew where it was going. There was music there, and some dancing. And then, just as the first song finished, and the applause rang out against the old stones, a figure stepped from out of the mist.

They said it was a man, though no one quite agreed on the details. Some saw a woman in green. Some, a child with silver eyes. Some swore he was covered in moss. Others said he had no shadow at all and a face of bone.

But all agreed on one thing:

He smiled.

Those who understood such things recognised him as one of the fey. They also smiled.

He sat down on a low wall and listened. Listened all day. And when the sun slipped low and the lanterns came on, he stood, took out a bone-white flute, and played a song no one had ever heard—and yet everyone somehow remembered.

That was the night gatherings changed. And what we now call festivals began.

They danced longer that night.

Sang in tongues long since forgotten.

Remade melodies from faded memories.

The stranger played three songs. Then disappeared back into the mist that he had arrived on. No one found footprints. No one knew where he went. No one saw him again,

But the hill—the hill saw all.

Those who heard the three tunes ran up the hill and rolled back down. Voices rose again, with mirth, music and laughter—louder than before. The sound echoed off the slope and rang out into the night, drawing others near. A feast was had. Travellers arrived. People greeted those long forgotten, and newcomers were made welcome.

The doors to the town were open.

‘Onan hag oll,’ a communal rallying cry was called.

And that’s why we call this the first festival. Not because music hadn’t been played before, or fires lit, or stories told. But because this was the first time that true change occurred.

The hill smiled.

So now, let us gather once again. Let us set up the tents and string the lights. Sing the old songs and make up new ones. Raise our glasses and celebrate while we listen to the music of our soul—of our history—of our future.

And the hill will remember:

W.S.Hudson

Festival update:

We are pleased to announce that it was a huge success—and the start of many more. Here are some photos capturing the fun of the day.

Help in promoting the event.